Study Hall: The Idiot

Cast of characters, themes, helpful details, and upcoming lectures to correspond with our analysis

Is it true, prince, that you once declared that ‘beauty would save the world’? Great Heaven! The prince says that beauty saves the world! And I declare that he only has such playful ideas because he’s in love! — Ippolit, The Idiot

Hi scholars,

We’re officially at the halfway point of our Fall 2025 Curriculum. This time, we’re diving back into Dostoevsky with The Idiot. In my eyes, Crime & Punishment and The Idiot are companion reads. Where Crime & Punishment imagines redemption in an ultimately good world, The Idiot explores the opposite.

(Personally, I’ve always imagined the world of Crime & Punishment to balance on a morally clear axis, versus the rapidly shifting and morally decaying society of The Idiot.)

On January 13th, 1868, Dostoevsky wrote to his niece, Sophia Ivanova:

The main idea of the novel is to present a beautiful man… There is only one positively beautiful person in the world, Christ, and the phenomenon of this limitless beautiful person is an infinite miracle itself. The whole Gospel according to St. John is about that… I’d only mention that of all the beautiful individuals in…literature, one stands out as the most perfect, Don Quixote. But he is beautiful because he is ridiculous. Wherever compassion toward ridiculed and ingenious beauty is presented, the reader’s sympathy is aroused. The mystery of comedy lies in this excitation of compassion.

To sum it up plainly, the question at the heart of The Idiot is the theology of beauty. Can beauty, ultimately, save the world?

Before we move on, here are some helpful links to help you navigate any resource you might need, including:

Study Hall (linked straight to the club on Fable)

The Idiot boasts a larger cast of characters. For the sake of ease, I’ll organize this list in two different categories.

Major Characters

Prince Lev Nikolaevich Myshkin: The central character and the novel’s eponymous “idiot.”

Aglaya Ivanovna Epanchin: The youngest daughter of General and Mrs. Epanchin. The other characters in the novel recognize her as the most beautiful of her sisters (Alexandra and Adelaida).

Nastasya Filippovna Barashkov: Another stunning beauty, but in a more haunting way than Aglaya. She has a commanding presence throughout the novel.

Parfyon Semyonovich Rogozhin: Rogozhin is the opposite of Myshkin. If Myshkin is innocence, purity, and beauty personified, Rogozhin is cruel, greedy, and corrupt.

Lizaveta Prokofyevna Epanchin (Mrs. Epanchin): The wife of General Epanchin and the mother of Aglaya, Alexandra, and Adelaida. Myshkin is a distant relative of hers.

Gavrila Ardalionovich Ivolgin (Ganya): The son of General and Nina Ivolgin and brother of Kolya and Varya. He’s arrogant, greedy, proud and works for General Epanchin.

Lukyan Timofeevich Lebedev: A clerk who is a “know-it-all” concerning the matters and gossip of society.

Ippolit Terentyev: A 17-year-old friend of Kolya’s and nihilist.

Varvara Ardalionovna Ivolgin (Varya): Only daughter of General and Nina Ivolgin and sister to Ganya and Kolya. She also marries the wealthy Ptitsyn to save her family.

General Ardalion Alexandrovich Ivolgin: Ganya, Kolya, and Varya’s father and Nina’s husband. He is a drunk with a tendency to embellish the truth.

Nikolai Ardalionovich Ivolgin (Kolya): The youngest, teenage son of General and Nina Ivolgin. He’s also Ganya and Varya’s younger brother.

Afansy Ivanovich Totsky: Wealthy, high-ranking middle-aged man and previous guardian of Nastasya.

Antip Burdovsky: One of the young nihilists in the novel.

Princess Belokonsky: The grandmother of the Epanchin girls (Alexandra, Adelaida, Aglaya).

Minor Characters

General Ivan Fyodorovich Epanchin: Husband to Lizaveta and father to the Epanchin girls. He was a common soldier with limited education who rose through the ranks in Russian society.

Alexandra Ivanovna Epanchin: Eldest daughter of General and Mrs. Epanchin

Adelaida Ivanovna Epanchin: Middle daughter of General and Mrs. Epanchin

Pavlishchev: A friend of Myshkin’s father who paid for Myshkin’s treatment in Switzerland.

Professor Schneider: The doctor who treats Myshkin in Switzerland

Ferdyshchenko: A crude man who hangs around Nastasya.

Marie: A poor woman in Switzerland who was ostracized in her village.

Mrs. Nina Alexandrovna Ivolgin: Wife of General Ivolgin.

Ivan Petrovich Ptitsyn: Varya’s husband and friend of Ganya.

Mrs. Terentyev: Mom of Ippolit.

Darya Alexeevna: Wealthy friend of Nastasya’s.

Salazkin: Lawyer.

Prince Shch: Adelaida’s husband.

Evgeny Pavlovich Radomsky: Intelligent, high-ranking man who is vying for Aglaya’s attention.

Vera Lukyanovna Lebedev: Lebedev’s adult daughter.

Keller: Part of the group of nihilists (Burdovsky, Ippolit, and Doktorneko).

Vladimir Doktorenko: Lebedev’s nephew and nihilist.

Chebarov: Burdovsky’s lawyer

Prince N.: High-ranking man with a reputation for being a player.

Ivan Petrovich: Pavlishchev’s cousin.

This novel is so rich and full of depth that I’m chomping at the bit to share my observations and dive into analysis. But I’ll save that for the club. For now, here are some themes to guide your reading:

Innocence vs. foolishness

Money, greed, and corruption

Social hierarchy, authority, and rebellion

Absurdity and nihilism

Passion and violence

Christianity

Tracking these would be a great start; however, if you want to excavate your way to the core of this novel, here are additional guiding themes to be on the lookout for:

The nature of man in the face of death

The nature of truth

Greatness and originality

Russian identity

Feminism

The theology of beauty

Eroticism (this was a confusing one to track, but oh so juicy)

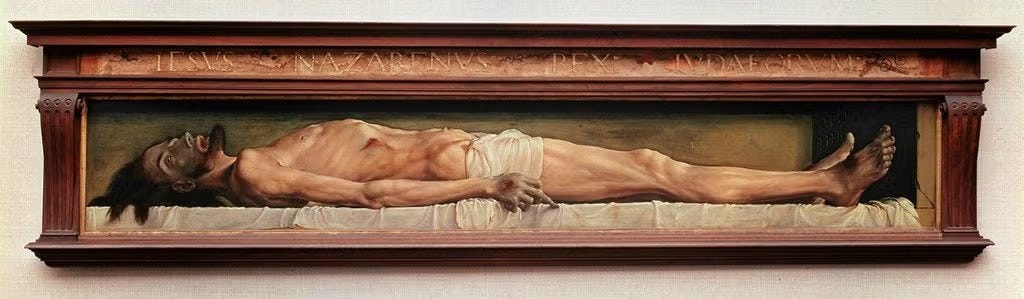

This striking painting by Hans Holbein is the gravitational center of this novel. Dostoevsky came face to face with this very painting in the Kunstmuseum Basel in 1867. In her memoirs, Anna Grigorievna, Dostoevsky’s second wife, recalls:

On our way to Geneva, we stopped for a day in Basel to see a painting in the museum there that my husband had heard about. This painting by Hans Holbein depicts Christ who has endured inhuman torment, already taken down from the cross and decaying. His bloated face is covered with bloody wounds and his appearance is terrible. The painting had a crushing impact on Fyodor Mikhailovich. He stood before it as if stunned. And I did not have the strength to look at it – it was too painful for me, particularly in my sickly [pregnant] condition – and I went into the other rooms. When I came back after fifteen or twenty minutes, I found him still riveted to the same spot in front of the painting. His agitated face had a kind of dread in it, something I had noticed more than once during the first moments of an epileptic seizure. Quietly I took my husband by the arm, led him into another room and sat him down on a bench, expecting the attack from one minute to the next. Luckily this did not happen. He calmed down little by little and left the museum, but insisted on returning once again to view this painting which had struck him so powerfully.

Dostoevsky’s personal remarks about the painting are injected into the text of The Idiot, with Myshkin echoing his thoughts early in the novel:

One can lose his faith from a painting like that.

It’s important to note here that in Russian tradition, Orthodox iconography would not allow for such a depiction, as icons are typically painted confronting the viewer directly. This is Christ, not as an icon, but as flesh. Damaged, destroyed, dead. Its presence is aggressive, aided by its dramatic dimensions that mimic a life-sized coffin (30.5 cm × 200 cm — that’s a foot tall and 6 feet wide).

Since this painting is such a crucial piece to the understanding and analysis of this novel, I’m hoping to host an art historian for one of our Study Hall Lectures.

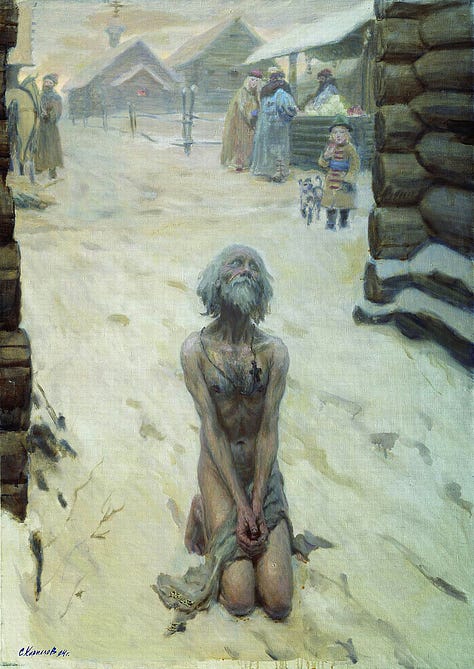

There’s an archetype in Russian folklore known as Yurodivy, or the Holy Fool. Yurodivy is often depicted as a social outcast, someone who doesn’t fit into “normal” society, is seen as foolish and feeble, but has access to truth. It is because he is an outcast that he is a truth-teller. In Russian Orthodox Christianity, Yurodivy is a saintly figure, an image you should keep in mind as you meet our Christ-like prince.

There are a few tidbits about Dostoevsky’s own personal life that could help you color the text of The Idiot a little more vividly:

Dostoevsky suffers from epilepsy, a trait that Myshkin shares.

At the age of 28, Dostoevsky was set to be executed by firing squad, only to be saved moments before. His death sentence for allegedly participating in anti-government activities was turned at the very last minute on the Tsar’s command, commuting his death sentence to four years in a Siberian prison camp.

The Idiot was written abroad between Switzerland and Italy. Specifically, Florence played a crucial role in the novel’s inspiration, as Dostoevsky was exposed and therefore greatly influenced by the art and beauty of the city. It was in Florence that Dostoevsky finished The Idiot. In his letters, Dostoevsky expresses about the city:

When the sun shines, it is almost Paradise. Impossible to imagine anything more beautiful than this sky, this air, this light.

It’s quite difficult to curate a moodboard based on The Idiot, solely because it contains multitudes and layers. On one hand, I’m tempted to fill the moodboard with scenes of high society and dachas, but doing so might give off the wrong atmosphere, turning it into something more suitable for Jane Austen. And filling it with moody studies, most often associated with Dostoevsky’s “personal brand” (as deemed by the internet) isn’t accurate either.

The route I’ve decided to take includes both. The brighter notes and embellishes of the upper echelon, and the shadows that call forth deep contemplation.

As for the playlist, this features a lot more Tchaikovsky instead of Rachmaninoff (as previously seen in Crime & Punishment). There’s a lighter, more optimistic feel to this playlist, as Myshkin’s purity is such a warming and loving presence, you can’t help but feel a semblance of hope against the gritty world. But there are moments of solitutde and contemplation as well. It’s why this particular Prelude & Fugue from the first book of J.S. Bach’s The Well Tempered Clavier felt fitting.

I also added Prokofiev’s “The Young Juliet,” from Romeo and Juliet, Op. 75 (not Op. 64), because it balances so perfectly an innocence and aloofness, but is later weighed down by the ominous theme in “Romeo Bids Juliet Farewell.”

(The entire Romeo and Juliet piano suite has such a special place in my heart and performance repertoire, so I will always direct listeners to the piano arrangement more often than the orchestral score.)

J.S. Bach — The Well Tempererd Clavier I, Prelude & Fugue No. 4 C♯ minor BWV 849 (This piece is particularly interesting and it is what I think of in relation to the Christ-like themes of the book. The main subject of the fugue [2:25] consists of five pitches, introduced right from the jump. It is said to resemble a cross on the musical staff, and the motif is thought to symbolize the crucifixion, originated from the Advent chorale, “Nu komm, der Heiden Heiland.”)

Prokofiev — “The Young Juliet,” from Romeo and Juliet, Op. 75

There’s so much I want to say about this novel already, but I want to leave this post strictly to information to help you analyze the novel and deepen your experience of reading it. My thoughts? I’ll save that for our discussions in Fable and our live discussion at the end.

For now, here’s our bulletin for upcoming lectures for The Idiot:

Ekaterina Drozdova: Understanding Dostoevsky’s Idiot

I’m so excited to welcome Katya Drozdova as our first lecturer for our reading of The Idiot. Katya is the founder of the Russian Language Center in Singapore, and she’s a professional teacher of Russian as a foreign language with an MA’s degree in Philology from Sholokhov Moscow State University. She’ll be guiding us through:

Facts from Dostoevsky’s biography and Russian history that’s helpful to know when understanding his work

How Dostoevsky is seen by Russians versus the foreign point of view

Helpful-to-know Russian language

Colors in The Idiot

Ekphrasis and the paintings that inspired The Idiot

The similarities between Myshkin and Jesus

We’ll also have a second lecturer for this novel. I’ve dropped a few unconfirmed details in Fable, but our second lecturer will be an art historian. I’m working on confirming a guest, but TBD on that as we find the time to schedule her in. Details to come as soon as we’ve locked things in.

Our discussions of Crime & Punishment and The Tempest have been incredible so far, and I’m immensely grateful for all your time and dedication to reading, learning, and discussing. Study Hall has been such a passion project of mine, and the only reason why I’m able to invite lecturers is because of you guys. I’m very careful with the brand partnerships I take on, as I care very deeply promoting overconsumption over things people don’t really need.

I’m not a full-time content creator and I’m tremendously lucky to have a job I love. Which is why every Substack subscription and paid partnership goes back into Study Hall through these lectures.

Thank you guys so much for your time and attention, but most of all, thank you for your dedication to engaging with these texts through a critical lens. Time is precious these days, especially since the world we live in demands we trade it for cash. The fact that you would willingly engage and participate in Study Hall is something I don’t take for granted.

I’ve put all of the music into a spotify playlist for myself, in case anyone else wants it here’s the link: https://open.spotify.com/playlist/6kl2J9rfkpxNM6tqMnM8Ay?si=4012x4_HTse0R9HKtLjMLQ&pi=G137o30fQhy3_

Picking up my copy today! I didn't have the time to dedicate to C&P so I haven't read any Dostoevsky before, though I've been meaning to for years. I've read other Russian classics but not one of his. Thank you for listing some of the themes and motifs to pay attention to! Makes it less intimidating and easier to engage with the book on a first read if I know what to keep an eye out for 🙏